“Read this,” said a friend. “Itʼs different.”

For the first time I was to be transported to the world of an African village by a writer whose words felt authentic.

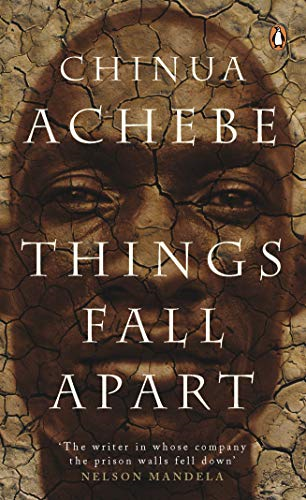

Chinua Achebeʼs 1958 novel, Things Fall Apart, tells the story of how the twin-impacts of colonialism and mission-focused Christianity destroyed the traditional Igbo (pronounced ‘Ee-boʼ) society of present-day eastern Nigeria. What I found so extraordinary about this book is the writerʼs evident knowledge and understanding both of traditional Igbo village life and also the local Christian church. How could one mind know both so well? I did a bit of digging and found out.

Achebeʼs parents were both Christian converts. When his father retired and went back to his native village the young China was five years old. He grew up among a wider family that included plenty of members who had not converted to the new religion. His parents remained respectful of Odinani, the religious practices of their traditional community. His mother and sister told young Chinua the old Igbo stories. And village life went on all around him with the celebration of traditional festivals.

So Chinua Achebe grew up on the cusp, with first-hand experience of the life of a traditional African village alongside first-hand experience of the Protestant Church Mission Society. Through this he was provided with the first steps of an education that made it possible for him, later, to write an English-language novel.

The dynamics of Things Fall Apart hinge around three generations of a family where son finds himself in reaction against father. Okonkwo, the main character, is in reaction against his father Unoka, a gifted musician who comes to fulfilment annually at the time of the major festival but is required to spend the rest of the year farming. In this he is a complete failure and to the unending shame of Okonkwo falls into ever-accumulating debt. Okonkwo reacts by working zealously in starting his own farm. Excelling in matters of strength he becomes a champion wrestler and he makes it an unquestioned rule to suppress any tendency towards sensitivity and reflectiveness in emotional life. This over-reaction becomes his Achillesʼ heel and leads him towards a terrible misjudgement in an incident that impacts hugely on his own son, Nwoye, who has inherited his grandfatherʼs sensitivity.

A woman is murdered by a man from a neighbouring village. To avert war the offending village provides a new bride for the widowed man and a young boy who is destined to be killed as an atoning sacrifice. But the boy, Ikemefuna, is not killed at once. Instead he is taken into Okonkwoʼs household where he befriends Nwoye and becomes generally esteemed and liked. When the local Oracle deems it time for Ikemefuna to be slain he has grown to regard Okonkwo as his own father. A tribal elder advises Okonkwo to have nothing to do with the killing but in his over-reaction against sentiment he cannot allow himself to stay away. Appallingly, as Ikemefuna turns to him in appeal, Okonkwo deals the final blow. The negative impact of this on his own psyche is felt the more keenly because it is a season when there is little to do on the land and time hangs on his hands. Still, he tries to suppress his emotion. His son Nwoye feels no such inhibition; instead, he has a sense that something in his own psyche is under threat, giving way.

Nwoye has felt this once before. It was the traditional practice for twins to be left to die in the forest. When one day Nwoye hears the cries of two such condemned infants, he has that feeling. It is repeated, even more keenly, in the incident involving his own father and his dear friend. In time, to Okonkwoʼs unspeakable disgust and contempt, Nwoye will become a Christian convert. His impulse towards Christianity may be seen as an impulse towards compassion.

In terms of world history this impulse to compassion can be seen to arise in Buddhism and the later prophets of the Hebrew scriptures. It pre-dates Christianity but is given full expression in the Gospels. Earlier tribal societies tended to be bound by imperatives of ritual purity where considerations of compassion carry no weight at all when placed on the scales against the requirements of the rite.

In the British Isles there are stories of a time when druids became aware of the life and death of Christ and some were moved to incorporate the radical compassion they saw in Jesus into their own tradition. What emerged from that fusion was the Céile Dé (Culdee) Tradition. The Scottish story of Bride as the midwife of Christ is also an echo. In this story Bride was brought up on Iona with Mother Nature as her only teacher. Longing for a more compassionate way of life she is transported to a cave in Palestine where she becomes Maryʼs midwife and herself suckles the infant Jesus. In that exchange Bride teaches Christ about Natureʼs ways; in return he teaches her Compassion. Transported back to Iona after forty days Bride imparts the new teaching to the druids there.

I was reminded of this story in reading Things Fall Apart. And I found myself thinking: What if? What if the missionaries had told the stories of the gospels and left it to the local people to respond to them as they felt moved? What if in Britain the Celtic church had not been suppressed and a more nature-respecting thought-world had been our norm? This theme is also explored in A G Rivettʼs forthcoming book, The Priest’s Wife, second book of The Isle Fincara Trilogy.

But instead Christianity has been allied to power structures: first that of Rome; then those of the later empires of the Western world. In so doing its central teaching of compassion has been compromised time and again. In his fiction Achebe dramatises one small incident when Okonkwo and his tribal elders are tricked by a colonial kangaroo court and Okonkwo faces the unbearable fact that the way of life he grew up in can never be recovered; is forever gone.

Gillian PB