With The Godmother, I begin a short series of occasional blog posts on novels about women who, against the odds, arrive at some form of emancipation. What form that takes depends, not only on the opportunities presented to the women whose lives we explore, but also, very much, on the start each had in life. And each presents a particular question. In this case – can you be too honest?

Hannelore Cayreʼs deftly-handled tale of how a court translator turns (soft) drug dealer introduces us to Patience Portefeux (which translates as Patience Carryfire), a woman who grew up in circumstances that were bizarre, distinctly shady and – just on family holidays when they wouldnʼt be observed by anyone who counted – occasionally opulent. The best influence in her life is Bouchta, an illiterate Black house servant who brings a measure of reliability, consideration and humanity to her life until her mother, who wants him gone, hits on the idea of teaching him to read. At which point, arriving at his own emancipation, Bouchta takes off, leaving behind a seventeen-year-old who, thanks to his efforts, has grown up not completely emotionally scarred.

Iʼm going to fast-forward here to the time when Patience, married to a wealthy man she really loves and with two young daughters, finds herself suddenly and shockingly widowed. At which point, to borrow her own words, her life turns to shit. And she, in the midst of her grief, is faced by the unforeseen imperative of having to earn her own bread. Largely due to Bouchta, she is fluent in two Arabic dialects, on the strength of which we learn she had earlier gone on to university studies in Arabic. This equips her to start work for the Parisian police as a translator of tapped phone calls between North African drug-dealers importing cannabis into France. She does this for 25 years. But we learn thereʼs no pension-scheme, and any possible savings she could have made have been swallowed up by the needs, first, of raising daughters, and then, of paying for her motherʼs care-home fees. When a combination of circumstances gives her the opportunity to obtain a very large quantity of high-grade cannabis, the spectre of her bleak financial future recedes. She becomes – the Godmother.

Are you the kind of reader who asks, If Iʼd been in her place, what might I have done? Might you, like Patience, have regarded importing a soft drug like cannabis as admittedly illegal but not really so bad? If so, would being law-abiding have been a more compelling motivation than providing for your old age and giving your daughters the independence of a home of their own? Hannelore Cayre, herself a criminal lawyer, makes it clear itʼs much easier at least to look morally upright when you have security and means.

So … can you be too honest? And what does that mean, anyway? Does being honest mean keeping the law? Or always telling the truth, factually? Or could it mean remaining true to the hierarchy of values that guide us in life? And which may differ, in some respects, from one person to another.

Before Patience Portefeux turned Godmother, she entered into a relationship with Philippe, a charming and upright policeman who ends up being appointed to the role of head of the drug investigation squad. When this promotion took place, Patience was happy for him. But at that point she had not commenced her illegal activities. All through the events that follow the life-changing moment when – aided by the retired sniffer dog she rescued from being put down – she finds the cache of cannabis, she has been dating the very man society has tasked to be her nemesis. At length, having achieved the security she seeks, Patience sensibly throws in the towel as drug dealer. (But not before witnessing various of her contacts imprisoned or even, she suspects, killed.) It is only then, through the kind of carelessness no human can ever be sure of avoiding, that she leaves around the clue that lets Philippe put two and two together. At which point, having, ʻin a fraction of a second … aged a thousand years,ʼ he disappears from her life for good.

Repeatedly, Patience has assessed Philippe as being too honest. With this in mind, I found myself imagining an alternative scenario. I imagined him taking a deep breath, asking her why she did it, and being willing to listen. Really listen. If he had understood her story as Hannelore Cayre has made sure we, its readers, have done, it might have been life-transforming. He might have grown as a human being. I donʼt underestimate the practical challenges that would have faced him. Made more aware of the double standards inherent in society, would he – should he – have found some way to carry on that he could have lived with? Humbly realising he is no better than anyone else. Because we all have to earn a living.

Thereʼs a concept in academic theology called structural sin. It basically means that if we go along with societyʼs norms, we will inevitably be compromising the highest moral standards somewhere. How we do this may be conveniently hidden from view, and itʼs right and proper to take some care to try to avoid benefitting from malpractice. But if we really went to the trouble of finding out everything thatʼs gone into all the products and services we use, and all the consequences of production, we may find we have little time for anything else. The uncomfortable truth is that if we choose to have nothing at all to do with anything thatʼs not absolutely squeaky clean, we may find it hard to stay afloat.

I remember once reading an essay by the Indian guru Rajneesh. From what I recall, he said that if you wanted to be truly authentic, absolutely honest, you would definitely get crucified in some way. He was thinking about Jesus and the Easter story, of course. And recognising that most of us just arenʼt up for that.

So what do we do? Beat ourselves up every day? Give up? Or do our best, and humbly recognise that our best will never be good enough. The language isnʼt very fashionable, but, as the preachers say, weʼre all sinners in need of forgiveness. Itʼs just the way it is.

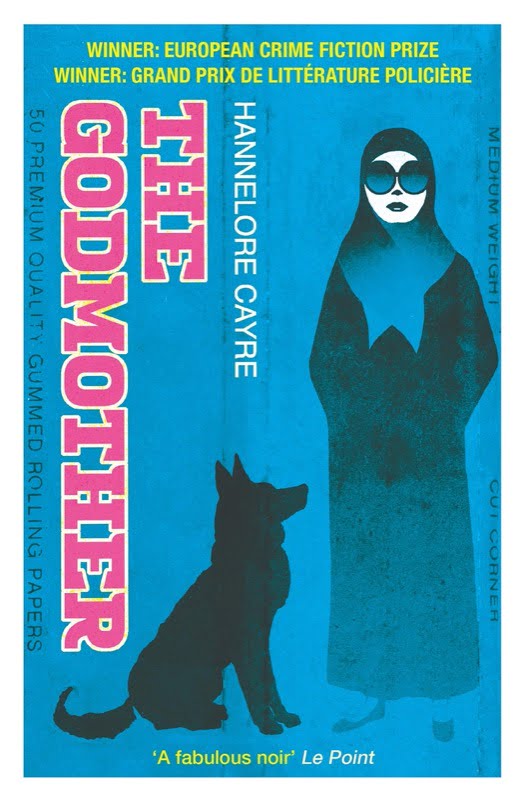

La Daronne was first published in French in 2017, and in English in 2019 as The Godmother.

Gillian PB