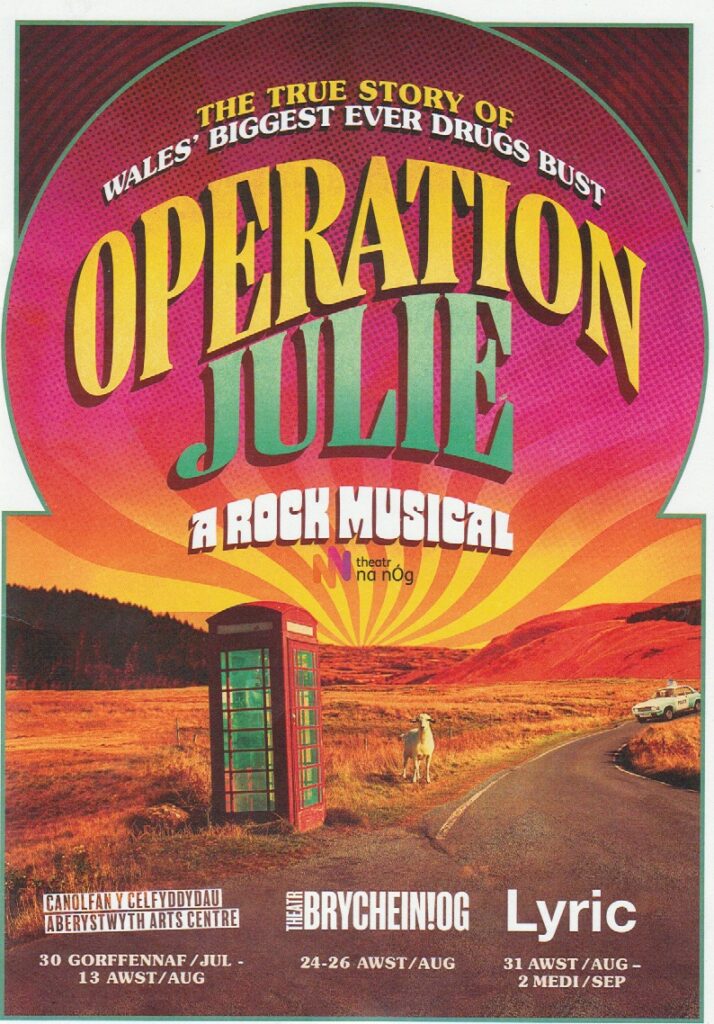

We went to see Operation Julie, the new rock musical from Theatr Na nÓg that premiered in the Aberystwyth Arts Centre, toured to Brecon, and then to the Lyric at Carmarthen, which is where we saw it on 31st August.

Operation Julie was the code name given to a 1970ʼs police operation that busted an LSD manufacturer (the chemist, Richard Kemp) and distributor (Alston Hughes, widely known as Smiles) who lived within six miles of each other near Tregaron in mid-Wales. How come thereʼs a musical about this? Well, partly, the story had its humour. Undercover police appear disgused as hippies and bird-watchers; on the day of the raid a policemanʼs wife, wanting to have a word with her husband, actually knocks on Smilesʼ door to ask if heʼs got there yet. And Kempʼs wife Christine Bott, a doctor at Bronglais Hospital in Aberystwyth, breeds a goat that wins the red rosette at The Royal Welsh Show. On a more serious note, it appears from a statement by Kemp, written at the time of these events, that he was an idealist with a mission. An excerpt from his ʻMicro-doctrineʼ is printed at the back of the programme. Hereʼs a quote:

“It is my experience and that of many of those I know that LSD helps make one realise that happiness is a state of mind, not ownership. Before too long, our planet will be facing untold challenges … Temperatures will soar. Sea levels will rise. Animals will perish. Natural resources will evaporate before our eyes before we have a chance to come up with a plan B … Politicians, business men, moguls, theyʼll step on the throats of their own people to save their billions, while the earth is crumbling apart beneath their feet … Then youʼll see what real anarchy is like.

We need a revolution in peopleʼs minds, we need a spark to put the world on the road to some sort of survival. And that wonʼt happen, not until we accept a lower standard of living … Acid … is a catalyst. Itʼs not a means to an end but itʼs a signpost pointing the way.”

Wanting to find out more about the issues, I carried out an internet search, turning up both journalistic sites and academic papers. My researches revealed that, in stark contrast to heroin, LSD – a synthesised form of an extract from the ergot fungus that grows predominantly on rye – is not addictive; there is no known toxic dose, and LSD-related deaths have been found to include other factors. But it can give people a bad trip or a range of unpleasant physical effects, mostly short-lived, of which perhaps the most disturbing is unconsciousness. It can also tip vulnerable people into psychosis. The upside is the mind-clearing change in perspective experienced by many people who, after taking a suitable dose, enter into a state of wonder and awe. We watched a Netflix documentary series, How to Change Your Mind, based on a book with the same title by Michael Pollan. It was from this that I learned of the research that went into the use of LSD from the 1950s to 1970.

In the sixties, LSD got out of the lab and became a so-called recreational drug. People started dropping out, and itʼs been conjectured that when Nixon banned LSD in 1970, it was because young men were refusing to go to fight in Vietnam. Then LSD became classed as a ʻSchedule 1 substanceʼ – an illicit drug with no medical use. “The miracle drug suddenly became a Satan drug,” wrote James Fadiman, a prominent researcher who, at Stanford University, once offered 100 mcg of LSD to 40 scientists who were feeling stuck in their own research. He claims that every one of them went on to come up with a satisfactory solution. A number of scientific and technological advances have LSD in their background – for example, PCR (polymerase chain reaction), a technique first thought of by Kary Mullis while under the influence of LSD, and recently seen in the PCR-testing so widely used during the covid pandemic.

For thirty years, the Schedule 1 substance classification held. But today LSD is back in the lab, with focus on micro-dosing designed to enable people facing the challenge of a terminal diagnosis to better prepare for their passing, or to enable people suffering chronic depression literally to change their minds. Ayelet Waldmanʼs book, A Really Good Day, gives an account of one womanʼs experience. “I’m back! I feel like myself again,” Waldman declared in Pollan’s documentary, comparing her experience of LSD micro-dosing favourably with that of other anti-depressants sheʼd taken.

LSD can give people the lived experience of what otherwise can feel like abstract statements: We are all inter-connected. We are all one. Or, as Michael Pollan put it: Love is the most important thing in the universe. You canʼt live constantly in that experience, but, experienced once, you can remember it and refer back to it through your daily life.

Because of this, beyond the medical applications currently being researched, itʼs possible to imagine that one day there could be retreat centres for the administration of LSD and other psychedelic drugs. They would need a staff competent in assessing clients, screening out the vulnerable, administering a suitable dose, and providing a setting that can hold retreatants through the exceptional experiences they may undergo. Mind-set and setting have been found to be key in influencing the experience of psychedelic drugs. (The root meaning of psychedelic can be translated as ʻmind clearing,ʼ from the Greek psyche, meaning mind or soul, and delos, meaning clear or manifest.) That is a powerful argument as to such LSD and other psychedelic drugs shouldn’t be regarded as merely recreational, but approached with caution and an intent that seeks a long-term positive outcome.

All this relates to The Seaborne, recently published in a new edition by Pantolwen Press, and to The Priest’s Wife, second book of the Trilogy, due out in April 2023. In the former, the wise woman, Mother Coghlane, prepares psychedelic herbs which assist with Dhion’s inner transformation. In the latter, Morag has a very different experience when, without any preparation, she ingests a psychedelic fungus.

Gillian PB